Meiosis (DP IB Biology): Revision Note

Meiosis as Reduction Division

There are two processes by which the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell can divide. These are:

Mitosis

Meiosis

Mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells and is the type of cell division used for growth, repair of damaged tissues, replacement of cells and asexual reproduction

Meiosis gives rise to cells that are genetically different from each other and is the type of cell division used to produce gametes (sex cells)

During meiosis, the nucleus of the original 'parent' cell undergoes two rounds of division. These are:

Meiosis I

Meiosis II

Meiosis I

The nucleus of the original 'parent' cell is diploid (2n) i.e. it contains two sets of chromosomes

Before meiosis I, these chromosomes replicate

During meiosis I, the homologous pairs of chromosomes are split up, to produce two haploid (n) nuclei

At this point, each chromosome still consists of two chromatids

Note that the chromosome number halves (from 2n to n) in the first division of meiosis (meiosis I), not the second division (meiosis II)

This is why the first division of meiosis is also known as reduction division

During prophase I of meiosis homologous chromosomes pair up and are in very close proximity to each other

A pair of homologous chromosomes can be referred to as a bivalent

At this point, there can be an exchange of genetic material (alleles) between non-sister chromatids in the bivalent

The crossing points are called chiasmata

This results in a new combination of alleles on the two chromosomes (these can be referred to as recombinant chromosomes)

This exchange of genetic material is known as crossing over

Spindle fibres attach to the centromeres of the bivalents which pulls the homologous chromosomes to the opposite poles of the cell

The individual chromatids of each chromosome are still attached by their centromeres

Between meiosis I and II there is no replication of the chromosomes

Meiosis II

During meiosis II, the chromatids that make up each chromosome separate to produce four haploid (n) nuclei

At this point, each chromosome now consists of a single chromatid

Meiosis overview diagram

One diploid nucleus divides by meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei

The need for meiosis in a sexual life cycle

The life cycles of organisms can be sexual or asexual (some organisms are capable of both)

In an asexual life cycle, the offspring are genetically identical to the parent (they have exactly the same chromosomes)

In a sexual life cycle, the offspring are genetically distinct from each other and from each of the parents (their chromosomes are different, causing them to be genetically distinct)

The halving of the chromosome number during meiosis is very important for a sexual life cycle as it allows for the fusion of gametes

Sexual reproduction is a process involving the fusion of the nuclei of two gametes to form a zygote (fertilised egg cell) and the production of offspring that are genetically distinct from each other

This fusion of gamete nuclei is known as fertilisation

Fertilisation doubles the number of chromosomes each time it occurs

This is why it is essential that the chromosome number is also halved at some stage in organisms with a sexual life cycle, otherwise the chromosome number would keep doubling every generation

This halving of the chromosome number occurs during meiosis

In animals, this halving occurs during the creation of gametes

Sexual lifecycle overview diagram

Sexual life cycle

Down Syndrome & Non-Disjunction

Non-disjunction occurs when chromosomes fail to separate correctly during meiosis

This can occur in either anaphase I or anaphase II, leading to gametes forming with an abnormal number of chromosomes

The gametes may end up with one extra copy of a particular chromosome or no copies of a particular chromosome

These gametes will have a different number of chromosomes compared to the normal haploid number

If the abnormal gametes are fertilized, then a chromosome abnormality occurs as the diploid cell (zygote) will have the incorrect number of chromosomes

Diagram showing non-disjunction compared to normal chromosome separation

Image showing how chromosomes failing to separate properly during meiosis can result in gametes with the incorrect number of chromosomes

Down Syndrome

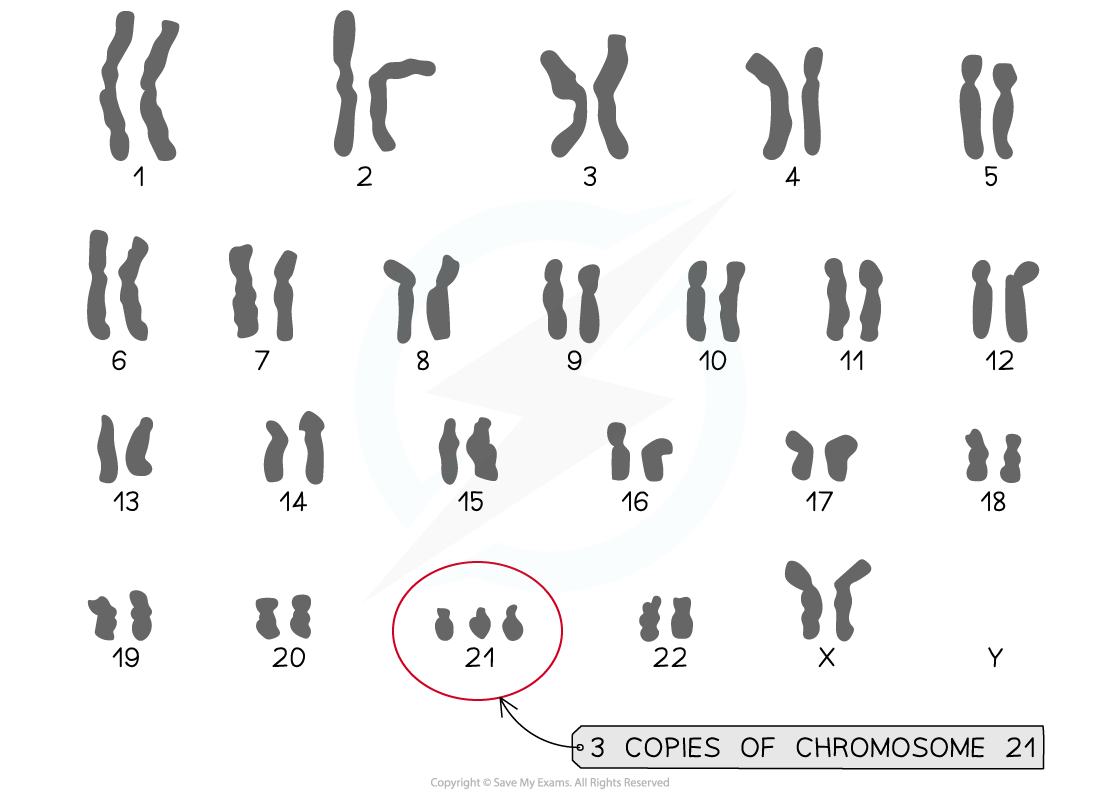

A key example of a non-disjunction chromosome abnormality is Down syndrome, also called Trisomy 21

Non-disjunction occurs during anaphase I (in this case) and the 21st pair of homologous chromosomes fail to separate

Individuals with this syndrome have a total of 47 chromosomes in their cells as they have three copies of chromosome 21

The impact of trisomy 21 can vary between individuals, but some common features of the syndrome are physical growth delays and reduced intellectual ability. Individuals can also suffer from issues with sight or hearing

There are other examples of non-disjunction which result in trisomy

Patau syndrome (trisomy 13) and Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) are very serious syndromes which result in many physical disabilities and developmental difficulties

The risk of chromosomal abnormalities increases significantly with age

The age of the mother is particularly important in the case of Down Syndrome as non-disjunction is more likely to happen in older ova

Karyotyping of the chromosomes in foetal cells can be used to identify chromosomal abnormalities

Foetal cells may be obtained by performing an amniocentesis or by chorionic villus sampling

Down syndrome karyotype diagram

A karyogram showing the karyotype of an individual with Down syndrome

Meiosis as Source of Variation

Crossing over and random orientation promote genetic variation

Having genetically different offspring can be advantageous for natural selection and therefore increase the survival chances of a species

Meiosis has several mechanisms that increase the genetic variation of gametes produced

Both crossing over and random orientation result in different combinations of alleles in gametes

Crossing over

At the start of meiosis, homologous chromosomes pair up with each other

As DNA replication has already occurred, each chromosome is made up of two sister chromatids

This means that a pair of homologous chromosomes is made up of four DNA molecules

A pair of homologous chromosomes is known as a bivalent

Each pair consists of a maternal and paternal chromosome

The pairing process resulting in the formation of a bivalent is known as synapsis

After synapsis has occurred, a process known as crossing over may occur

During crossing over, two non-sister chromatids (i.e. one chromatid from each of the homologous chromosomes) form a junction

At this junction, the two chromatids break and rejoin with each other

As these crossover events occur at exactly the same position on the two non-sister chromatids, this allows genes to exchange between the chromatids

Non-sister chromatids are homologous but are not genetically identical and this means that some of the alleles of the exchanged genes will be different

This process, therefore, produces chromatids with completely new combinations of alleles (that were not previously present in the DNA of the 'parent' cell)

This is because genetic material was exchanged between the maternal and paternal chromosomes

As these chromatids will eventually be split up into different gametes, crossing over is of great importance because it is a significant source of genetic variation between gametes

This ensures there is genetic variation in populations of sexually-reproducing species, which is key to a species' ability to evolve and adapt to changes in its environment over time

Diagram showing crossing over

Crossing over of non-sister chromatids leading to the exchange of genetic material

Random orientation of bivalents

At metaphase, during meiosis I, bivalents line up at the cell equator as they prepare to separate

Spindle microtubules grow out from the poles of the cell and attach to the centromeres of the chromosomes

Each of the two homologous chromosomes in a bivalent is attached to a different pole

The orientation of the bivalents when they line up at the cell equator determines which pole each chromosome gets attached to (and eventually pulled towards)

The orientation of the bivalents is completely random

In addition, the bivalents also assort independently of one another (i.e. the orientation of one bivalent never affects the orientation of another)

Diagram showing random orientation

The orientation of bivalents lining up at the cell equator is random

The different combinations of chromosomes following meiosis

The number of possible chromosomal combinations resulting from random assortment is equal to 2n

n is the number of homologous chromosome pairs or haploid number

For humans: the number of chromosomes is 46 meaning the number of homologous chromosome pairs is 23 so the calculation would be:

223 = 8,388,608 possible chromosomal combinations

Unlock more, it's free!

Did this page help you?