Explain how the data in Extract A show that the market power of the Big Four banks is weakening against competition from smaller rivals

Case Study

Was this exam question helpful?

Exam code: 7136

Select a download format for 5. Perfect & Imperfectly Competitive Markets & Monopolies

Select an answer set to view for

5. Perfect & Imperfectly Competitive Markets & Monopolies

Explain how the data in Extract A show that the market power of the Big Four banks is weakening against competition from smaller rivals

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract E describes the British railway sector as a ‘natural monopoly’, which was split up into ‘no less than 100 pieces’ when it was privatised.

With the help of a diagram, explain why breaking up a natural monopoly in rail may affect long-run average costs

Extract E: Privatisation of British Rail

‘More competition, greater efficiency and a wider choice of services’, proclaimed the 1992 Government white paper that advocated the privatisation of British Rail. Two decades on, passenger journeys have more than doubled from 735 million in 1994–5, to 1.7bn in 2016–17

But how much of this is due to the benefits of privatisation, rather than factors such as increasing urban congestion and a rising population? The UK’s trains and tracks are more intensively used than in any other European market except the Netherlands. Investment is up, at around four times (in real terms) the £1.6bn a year it averaged in the late 1980s. The data on service quality are mixed. The UK performs well in terms of punctuality and reliability, but many journeys are uncomfortable. At peak hours 23% of London commuters have to stand. Instead of pushing British Rail into the private sector as a natural monopoly, the Government split it up and sold it in no less than 100 pieces between 1995 and 1997

Privatisation was supposed to unleash efficiencies that would justify the returns private operators demand for their services. However, a recent study shows that the cost of running the UK’s railways is 40% higher than in the rest of Europe. “The train you catch is owned by a bank, leased to a private company, which has a franchise from the Department for Transport to run it on track owned by Network Rail, all regulated by another office, and paid for by taxpayers or passengers,” says Prof John Stittle. Since 1996, government subsidies have almost doubled in real terms. Ticket prices are now 25% higher in real terms than in 1995 and 30% higher than in France, Sweden and Switzerland

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract C states that ‘There is ample opportunity for new players to enter the sector.’

With the help of a diagram, explain how the lowering of barriers to entry in the banking market might lead to lower prices and a situation in which banks make normal profit

Extract C: The rise of challenger banks

As the first new high street bank in 150 years, Metro Bank promises to operate distinctively: longer opening times than its rivals, instant debit cards for new account holders and eye-catching initiatives such as in-store dog water bowls. There are plans to grow its branch network from 48 to 110 by 2020. This bucks the UK trend for closing bank branches, more than 8000 of which have disappeared from high streets in the past 25 years. Metro Bank’s Chief Executive Officer said of the big banks: “They act like oligopolies are supposed to: they under-invest; under-serve and they take you for granted.”

Many of the major banks suffer from inefficient, outdated IT infrastructure which limits their ability to reduce prices. They may also suffer from diseconomies of scale, given the size of their workforce and the breadth of their operations. There is ample opportunity for new players to enter the sector

Metro Bank may take years to grab meaningful market share in the UK. Its straightforward business model involves opening new branches, collecting deposits and lending these funds to borrowers. This is safer than the riskier funding methods deployed by the some of the banks that failed during the financial crisis, but is unlikely to generate rapid growth. Even so, its customer focus puts pressure on dominant banks to improve their service

Source: News reports, August 2017

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract B (lines 12–14) states that ‘The Universal Postal Service obligations require Royal Mail to deliver letters and parcels to all parts of the country six days a week’.

With the help of a monopoly diagram, explain how the Universal Postal Service obligations are likely to affect Royal Mail’s costs and profits.

Extract B: The privatisation of Royal Mail Royal Mail has started a new chapter after the government ended 499 years of public ownership by selling off its remaining stake. Although critics have suggested that the government undervalued the company, total proceeds of the sale amount to £3.3 bn. The newly privatised company will have to cope with structural decline in the number of letters sent in the UK (Royal Mail has a near monopoly in this market), as well as fierce competition in the parcels delivery market, which is rapidly growing because of the growth of online shopping.

A review of Royal Mail is under way by the regulator Ofcom, triggered by concerns that the withdrawal of Whistl, a smaller rival in the door-to-door letters delivery market, means the postal operator has no competitive pressure to improve services and become more efficient. Ofcom is considering whether the price Royal Mail charges competing courier companies, such as Whistl or Amazon, to access its own delivery network are fair. It is also examining whether Royal Mail’s Universal Postal Service obligations are reasonable. The Universal Postal Service obligations require Royal Mail to deliver letters and parcels to all parts of the country six days a week, unlike its competitors. Some consumer organisations have claimed that increased competition in the parcel market has led to a worsening service for rural and remote consumers, including problems such as non-deliveries and lengthy journeys to collect undelivered items.

Competitive pressures on Royal Mail’s profits may require the firm to cut costs. Pay negotiations with workforce representatives are set to begin but the powerful Communication Workers Union is likely to fight any redundancies. Analysts say that this could make it harder for management to find cash for investments to boost competitiveness.

Source: News reports, October 2015

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain how the data in Extract A (Figure 2) show that the UK parcels delivery market is displaying dynamic efficiency

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Using the data in Extract A (Figure 1), calculate the three-firm concentration ratio in the UK parcels delivery market. Give your answer, as a percentage, to one decimal place

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain how the imposition of a tax on a good or service affects both consumer surplus and producer surplus

Critics of the world’s five most valuable multinational technology firms (Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft) argue that there ought to be greater government intervention to protect consumers’ interests. Several European governments are considering imposing new taxes on the revenues of such firms, rather than their profits

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain the factors a profit-maximising firm will take into account when deciding whether to shut down or to carry on operating, both in the short run and in the long run

Several loss-making retailers including Homebase, House of Fraser and Poundworld have had to decide whether to shut down operations or carry on while making losses. In contrast, the music-streaming firm Spotify was valued at $27 billion in 2018, despite never having made a profit in any year since it was founded. Spotify has been more focused on expanding market share.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Assess the view that price discrimination is always damaging

In December 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) announced a range of policies to prevent firms charging existing customers more than new customers. Firms supplying financial services, mobile phones and broadband are no longer allowed to discriminate against loyal customers renewing their contracts.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Discuss the validity of the traditional economic assumption that the main objective of firms is to maximise profits

Several loss-making retailers including Homebase, House of Fraser and Poundworld have had to decide whether to shut down operations or carry on while making losses. In contrast, the music-streaming firm Spotify was valued at $27 billion in 2018, despite never having made a profit in any year since it was founded. Spotify has been more focused on expanding market share.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Evaluate the view that a firm making low profits must be inefficiently managed

In the United States, corporate profits since 2010 have averaged 9% of GDP, compared to 5% in the 1990s. This is causing concern that the US economy is increasingly dominated by companies with monopoly power

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain how price and output are determined for a firm in a monopolistically competitive market, in both the short run and the long run

Roughly £18bn is forecast to be spent in the UK on advertising in 2017. Much of this will be spent by monopolistically competitive firms or oligopolies seeking to differentiate the products they sell to consumers.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Evaluate the view that government regulation of monopolistically competitive markets is unnecessary, and that polices to encourage competition and prevent the abuse of monopoly power should focus entirely on oligopolies and monopolies

Roughly £18bn is forecast to be spent in the UK on advertising in 2017. Much of this will be spent by monopolistically competitive firms or oligopolies seeking to differentiate the products they sell to consumers.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Assess the view that price discrimination is always damaging

In December 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) announced a range of policies to prevent firms charging existing customers more than new customers. Firms supplying financial services, mobile phones and broadband are no longer allowed to discriminate against loyal customers renewing their contracts.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain the likely impact on consumer surplus and producer surplus as an industry moves away from a competitive market structure to one that is dominated by a few large firms

In 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority issued a report which criticised a ‘situation where businesses charge higher prices to existing customers who stay with them, than they do to new customers’. However, according to Citizens Advice, some broadband and mobile phone companies continue to charge existing customers more than they charge new customers.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Evaluate the view that price discrimination is damaging for consumers

In 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority issued a report which criticised a ‘situation where businesses charge higher prices to existing customers who stay with them, than they do to new customers’. However, according to Citizens Advice, some broadband and mobile phone companies continue to charge existing customers more than they charge new customers.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Evaluate the view that technological change tends to bring industries closer to the market structure of perfect competition

Price comparison websites were used to purchase 53% of car insurance policies in 2017, improving competition and reducing prices for consumers. In other sectors, dominant firms such as Amazon have used innovation to capture market share. In the UK, 70% of online consumers say that Amazon is the first online retailer they visit when buying goods.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain why, in long-run equilibrium, monopolistically competitive markets are neither productively nor allocatively efficient

Some believe that government intervention in markets is undesirable because market forces promote creativity, innovation and efficiency. Others believe that competition policy is needed to prevent firms abusing their market power.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Discuss how the divorce of ownership from control may affect both the conduct and performance of firms

Aston Martin, the luxury car manufacturer, became a publicly listed company on the London Stock Exchange in October 2018, being valued at £3.89bn. The company had hoped to expand into new markets, enabling it to exploit economies of scale. However, following poor sales and weak profits, the company had lost 75% of its value by February 2020.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain how market contestability affects the performance of an industry

Some argue that privatisation of government-owned industries is necessary to improve efficiency. However, there are several cases where privatisation has simply transferred a monopoly from the state to the private sector. Nevertheless, such private monopolies are vulnerable to the threat of new entrants challenging their dominance.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Discuss the view that privatisation is always beneficial because it leads to improvements in efficiency

Some argue that privatisation of government-owned industries is necessary to improve efficiency. However, there are several cases where privatisation has simply transferred a monopoly from the state to the private sector. Nevertheless, such private monopolies are vulnerable to the threat of new entrants challenging their dominance.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

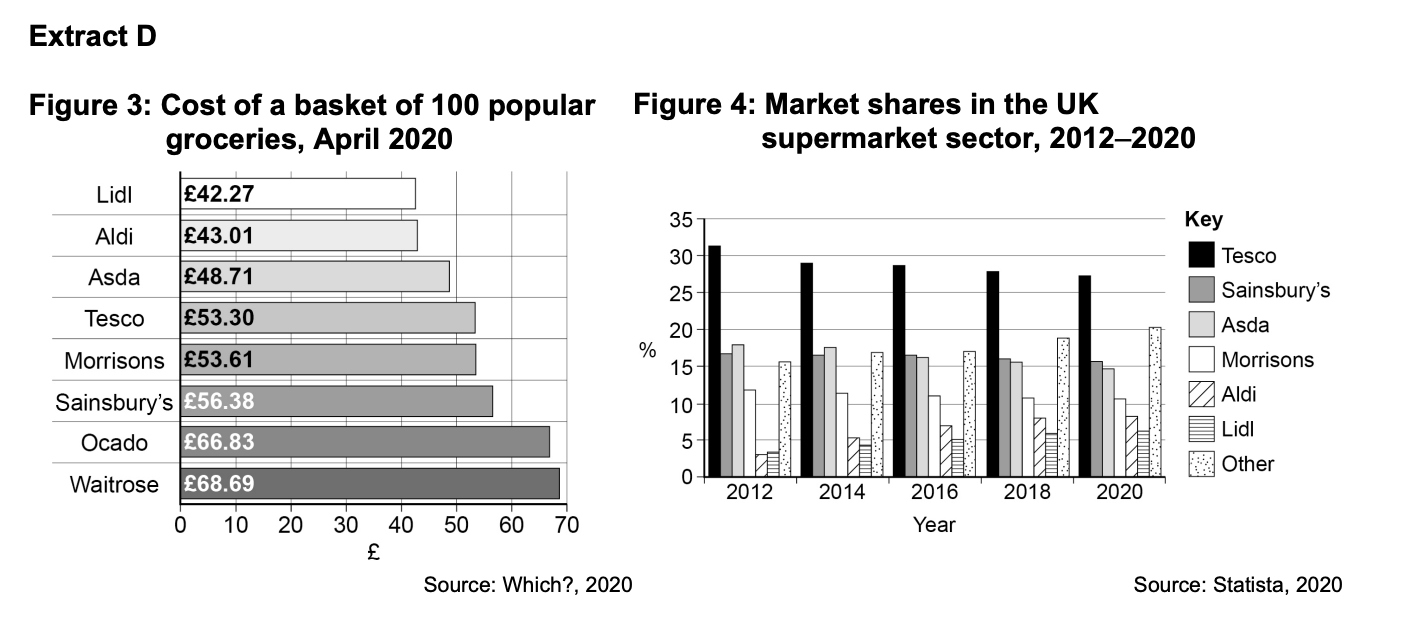

Explain how the data in Extract D (Figure 4) show that the supermarket sector is competitive.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract E (lines 16–17) states that, ‘Supermarkets set prices interdependently, and price wars look very likely.’

With the help of a diagram, analyse the impact on grocery consumers of interdependence between supermarkets.

Extract E: Have Aldi and Lidl reached their peak?

Aldi and Lidl, the German discount grocers which primarily sell through physical stores, have missed out as more sales have moved online. They are now trying some small scale 'click and collect' and other online options, and are hoping to win back business as the economic downturn prompted shoppers to seek out lower prices. However, industry experts say their recent rapid growth and competition from traditional supermarkets would make it harder for the discounters to take more business from rivals. The ‘big four’ UK supermarkets – Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda and Morrison's – have well-established home delivery infrastructure and were able to expand online delivery dramatically during the pandemic. This led to a doubling of the online share of the overall grocery market to 13% in just a few months.

Aldi and Lidl grew rapidly after 2008 as traditional supermarkets defended profit margins rather than sales. The discounters’ combined market share in the UK grew from 4% to 14% in a decade. However, this time the traditional supermarkets are expected to put up a tougher fight. Andrew Porteous, analyst at HSBC, said the big four were “all very conscious of the mess they made of the last recession. They have done well through lockdown.” “They will want to make sure they don’t give people any reason to go back to split shops” he added, referring to the practice of shopping for basics at a discounter and topping up elsewhere. Supermarkets set prices interdependently, and price wars look very likely. Analysts estimate the price gap between discounters and conventional supermarkets is now about 10–12%, against more than 20% a few years ago. Tesco has pledged to match Aldi prices on key items, while Morrisons recently cut prices on 400 basics, and Asda has indicated it will not be holding back from price reductions. Competition and investment in more stores have reduced the discounters’ profitability. Aldi’s profit margin fell from above 5% in 2013 to just 1.75% in 2018.

Source: News reports, 2020

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract E (lines 17–19) states that, ‘the price gap between discounters and conventional supermarkets is now about 10–12%, against more than 20% a few years ago.’

Evaluate the view that the supermarket sector is serving customers' interests well

Extract E: Have Aldi and Lidl reached their peak?

Aldi and Lidl, the German discount grocers which primarily sell through physical stores, have missed out as more sales have moved online. They are now trying some small scale 'click and collect' and other online options, and are hoping to win back business as the economic downturn prompted shoppers to seek out lower prices. However, industry experts say their recent rapid growth and competition from traditional supermarkets would make it harder for the discounters to take more business from rivals. The ‘big four’ UK supermarkets – Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda and Morrison's – have well-established home delivery infrastructure and were able to expand online delivery dramatically during the pandemic. This led to a doubling of the online share of the overall grocery market to 13% in just a few months.

Aldi and Lidl grew rapidly after 2008 as traditional supermarkets defended profit margins rather than sales. The discounters’ combined market share in the UK grew from 4% to 14% in a decade. However, this time the traditional supermarkets are expected to put up a tougher fight. Andrew Porteous, analyst at HSBC, said the big four were “all very conscious of the mess they made of the last recession. They have done well through lockdown.” “They will want to make sure they don’t give people any reason to go back to split shops” he added, referring to the practice of shopping for basics at a discounter and topping up elsewhere. Supermarkets set prices interdependently, and price wars look very likely. Analysts estimate the price gap between discounters and conventional supermarkets is now about 10–12%, against more than 20% a few years ago. Tesco has pledged to match Aldi prices on key items, while Morrisons recently cut prices on 400 basics, and Asda has indicated it will not be holding back from price reductions. Competition and investment in more stores have reduced the discounters’ profitability. Aldi’s profit margin fell from above 5% in 2013 to just 1.75% in 2018.

Source: News reports, 2020

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Extract C (lines 1–3) states: ‘The market for most generic drugs is oligopolistic, with just two or three manufacturers making each product. This enables significant economies of scale within firms, but also presents the risk of consumer interests being harmed.’

Using the extracts and your knowledge of economics, assess the view that the market structure of the pharmaceutical industry is damaging for consumers

Extract C: Is the market for pharmaceuticals working well?

The market for most generic drugs is oligopolistic, with just two or three manufacturers making each product. This enables significant economies of scale within firms, but also presents the risk of consumer interests being harmed. In 2019, US regulators accused 20 firms of colluding to raise generic drug prices by as much as 1000%. Combined with the monopoly for those drugs protected by patents, high prices and profits prevail in many parts of the industry. However, pharmaceutical firms argue that they take enormous financial risks in the search for new drugs. GlaxoSmithKline has spent just under £20bn on research and development over the past five years, while AstraZeneca spent nearly £30bn. These high development costs have led to new drugs becoming less profitable over the last decade. Pharmaceutical firms also provide thousands of highly skilled jobs and a reliable and safe product for consumers. Medicines and vaccines have played a crucial role in increasing UK life expectancy by 11 years since 1960. Over the last 40 years, cancer survival rates have doubled, and HIV/AIDS has been transformed into a manageable illness. UK firms are at the forefront of such developments and they make large profits in doing so. Many drugs have an extremely inelastic demand, as patients require them to maintain good health, which provides monopoly firms and collusive oligopolies with an opportunity to exploit their position. If this happens, the Competition and Markets Authority has the power to tackle the problem aggressively.

Source: News reports, 2019

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?

Explain how perfect competition should lead to outcomes which are both productively and allocatively efficient

Price comparison websites were used to purchase 53% of car insurance policies in 2017, improving competition and reducing prices for consumers. In other sectors, dominant firms such as Amazon have used innovation to capture market share. In the UK, 70% of online consumers say that Amazon is the first online retailer they visit when buying goods.

How did you do?

Was this exam question helpful?